BTT Faculty Features Series: Meet H. Timothy Lovelace

H. Timothy Lovelace, Jr., a noted legal historian of the civil rights movement, joined the Duke Law faculty in June 2020. Dr. Lovelace’s work examines how the civil rights movement in the United States helped to shape international human rights law. He has had a prolific and engaging career. In 2015, he received the Indiana University Trustees’ Teaching Award. During the 2015-2016 academic year, he served as a Law and Public Affairs Fellow at Princeton University. His scholarship has also received support from the William Nelson Cromwell Foundation, Indiana University New Frontiers in the Arts and Humanities program, and John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Foundation.

Lovelace earned his J.D. and Ph.D. from the University of Virginia. During law school, he was an Oliver Hill Scholar, the Thomas Marshall Miller Prize recipient, and the Bracewell & Patterson LLP Best Oralist Award winner. As a doctoral student in history, Lovelace was also a Virginia Foundation for Humanities Fellow and the inaugural Armstead L. Robinson Fellow of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies.

In this edited and condensed interview, Dr. Lovelace discussed his long ties to Duke, the importance of developing a mentoring network, and his career interests in the civil rights movement and its importance to the field of legal history with Black Think Tank’s Allayne Thomas.

What brought you to Duke after a successful career in Indiana?

The short answer is that in the Spring of 2019, I served as the John Hope Franklin visiting professor of American Legal History at Duke Law school and I loved my time there. It was just an incredible community. I went on the lateral job market last year and I ended up at Duke.

The longer answer is that I actually became acquainted with Duke Law when I was in graduate school. Guy Charles, a Duke law faculty member, is one of my mentors and he developed what is called the Emerging Scholars program, which helps scholars of color enter law teaching. He also developed the Jerome Culp Colloquium, which helps untenured scholars of color receive tenure. Jerome Culp was a Duke faculty member, who is now deceased, but was well-known for helping junior scholars of color.

Duke Law hosted annual conferences for both of these programs and I was one of the early members of the Emerging Scholars program. I participated in the Jerome Culp Colloquium until I received tenure and now I help to convene both programs. And so, these programs have literally transformed the legal academy. The Emerging Scholars program, for example, has placed people at schools like Stanford, Penn, UCLA, UC Davis, Indiana, Harvard, Georgetown, so it has been a wildly successful program.

Duke Law had been instrumental to my success as a junior scholar. I actually knew many Duke faculty members because of my formative experiences in those programs, so it was just a great community when I was invited to come back to Duke.

Could you tell us more about your research here at Duke and, in particular, your new book The World is On Our Side?

My scholarship explores how the civil rights movement helped to shape the development of international human rights law and my book flows from a number of earlier projects. In 1963 the United States was really struggling with its image abroad. Demonstrations in Birmingham erupted and children there were protesting nonviolently, only to be met with bruising fire hoses and snarling police dogs. 1963 was also the year that Medgar Evers was assassinated, martial law was declared in Cambridge, Maryland, and the year of the March on Washington.

The U.S. was really wrestling with its image abroad and so it became very involved in drafting the International Convention on the Elimination on All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which is commonly known as the UN Race Convention, to counter its negative racial perceptions, raise its global standing, and appeal to newly independent countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The United States selected a Black lawyer and a Jewish lawyer to represent the nation as the UN was drafting the worlds’ most comprehensive treaty on race. The Jewish lawyer was a lawyer for Dr. King; the Black lawyer was the Dean of Howard law school. They were both from the South, they were both WWII veterans – who better to fight the Soviets? And so the book tells the story of how this interracial, inter-faith coalition came together to represent the promise of American democracy and how they attempted to export U.S. Civil Rights law into the Convention. The idea was that if the convention looked like US Civil rights law, then the US could argue that it was actually at the vanguard of racial progress. The book has just been a lot of fun to write. I am in edits right now, and hopefully it will be in publication sooner rather than later.

What can the study of law teach us about the insurrection on the U.S. Capitol on January 6th?

You know, we are at a crossroads in our democracy. One of the fascinating lessons we gain from history and law is that there is a long history of white nationalists attempting to overthrow democratically elected governments. This happened throughout the Reconstruction period. At the beginning of Reconstruction, whites attempted to overthrow governments or attack former Black soldiers in cities like Memphis and New Orleans. In Colfax, Louisiana there was a race riot where whites literally stormed a courthouse and murdered dozens of Blacks. In 1898, we know that there was a Wilmington race riot led by white supremacists who overthrew a democratically elected government. While some Americans might look at what happened on January 6th, 2021 as being remarkable, and in many ways, it is remarkable – we had not seen the Confederate flag fly in the US Capitol by insurrectionists – our country also has a great and unfortunate history of white backlash, impunity, and even insurrection. It's also important to note the parallels in the impeachment of Donald Trump and Andrew Johnson. Both were impeached because they made menacing comments directed against the US, the country they took an oath to protect, so there are deep historical parallels there.

Is there a quote or a poem that is resonating with you recently?

My affinities for poems and quotes change seasonally. Recently I’ve been having conversations about what does freedom mean and in particular, I have been meditating on a quote from Angela Davis. She says that “freedom is a constant struggle”. Her assertion here is borrowed from a freedom song. In the wake of the election of Barack Obama many Americans said that we had entered a post-racial society, that we were on the way to the promised land. I never personally believed that, but what January 6th has shown all of us is that freedom is a constant struggle. The complacency that some people might have had in the wake of Barack Obama’s election was challenged by the racist backlash he soon faced. This is just part of the history of America: white supremacy evolves and when there has been racial progress, or even perceived racial progress, there is often backlash. And so, we are must remain vigilant and protect and improve our democracy. African-Americans have been at the forefront of this, pushing America to be all that it says that it is. The struggle remains and Angela Davis’ words ring true, just in a new way.

This is part of the history of America: white supremacy evolves when there has been racial progress, or even perceived racial progress...So we must remain vigilant and protect and improve our democracy.

What do you think are the major challenges for Black scholars learning to navigate academic spaces?

It is well documented that Black scholars throughout academia often face major hurdles in hiring, promotion, endure great service burdens, etc. I am grateful that I have had people around me who have helped to protect me from some of those problems. To be sure, I have still felt this weight at times, but I feel like I have been fortunate compared to some. One of the challenges I have seen is the struggles of Black scholars who do not have mentors around them who help to shepherd them through the entry level hiring process or the lateral hiring process, or people in the building who can speak up on their behalf, particularly for junior scholars who are more vulnerable than tenured scholars.

What would you say makes a good mentor and a good mentee?

I think empathy is critically important. Mentors should remember that they did not know everything when they entered the academy. Sometimes, this might mean taking more time to explain their advice or being sensitive to the mentee's professional insecurities while giving critical feedback. The challenge here is that sometimes people of color may not get the critical feedback that they need to advance their career. Instead, they may get very polite and uncritical advice because a mentor may not want to discourage a person of color's professional journey. Mentors have to strike a balance. I think that if the mentor delivers critical feedback with empathy, understanding, and mutual respect, then most scholars can respond positively and become the best versions of themselves.

For the mentee, be genuine. As mentees are developing relationships, they should not be instrumental, but genuine professional relationships. The other thing is to listen. It does not mean that the mentee have to take literally every word that your mentor gives you, but show gratitude and that the mentor is not wasting his or her time.

What are three pieces of advice would you have to Black faculty starting their position?

As I mentioned, first, have many mentors. Don’t simply have one mentor, and every mentor does not have to look like you. You need mentors for different parts of your professional career. Perhaps someone is a great reader of scholarship, perhaps someone else will connect you with people not only within your institution, but across institutions. So, have many mentors.

The second thing is become an expert in your field. You want to be part of the key conversations in your field and you want to be known as the next great scholar in your field.

The final piece of advice that I would offer is to remember that you will have a long career. When many junior scholars are hired, they want to do everything that they have dreamed of immediately. This might mean advising a large number of graduate students, mentoring other people, or being really engaged in the community. I believe that scholars should do all of those things, but you do not have to do them immediately. Part of being a good faculty member is being able to get tenure and thinking carefully about your time and your engagements. You will have a long career and have the opportunity to pay what others poured into you both forwards and backwards.

What are you looking forward to in 2021?

Professionally, scholarship is always at the front of my mind. I am looking forward to publishing my book, and then moving onto new projects. I am interested in the intersections of race, law, and religion. I am also interested in the business of civil rights, thinking about the evolution of corporate social responsibility during the civil rights movement. Personally, I hope to be vaccinated along with many, many more people, so that we can all travel, spend time with family and friends, and truly live in community again.

Could you tell me just a little bit more about your thoughts on the intersections of race, law and religion?

One of the themes that I plan to explore is the idea that many constitutional debates were also theological debates, such as the concept and period of Reconstruction––literally bringing God’s people back together. A second example is Redemption. Redemption was backlash to Reconstruction, and during this period, white nationalists in the South talked about ‘redeeming the South’ and ‘getting it back to a pure place’–– that Reconstruction had actually been sinful.

I would also like to examine constitutional and theological debates during the 20th century. Many scholars have written a lot about sit-ins, but I am really interested in pray-ins and the theological dimensions there. Why have a sit-in in church? What did that mean in terms of private property rights? What were the legal and theological implications of pray-ins for the construction and reconstruction of the body of Christ?

To finish, what would you consider one of the best moments in your career?

When I attended law school, I thought that I would become a social justice lawyer. My parents had been very involved in civil rights. My mother helped to desegregate schools in my hometown and my dad’s pastor was the president of the local NAACP. I grew up with this civil rights background, so I thought I would go to law school and have a social justice practice. Yet during law school, I, like many of my peers, began to apply to major law firms to work in the summer. Those summer internships turn into jobs when you graduate. I worked at a big firm during my law school summers and it was great experience in many ways.

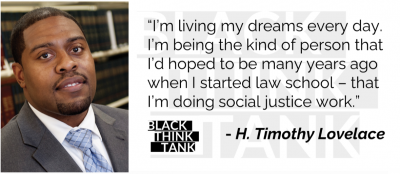

However, I also found myself on the wrong side of many of the cases that I worked on. My law firm was doing things like working with Big Tobacco while many poor people were being harmed by Big Tobacco. Every day I felt like I was having an existential dilemma at my desk. During those summers, I read a lot to decompress. I read law reviews in the evenings to sort of offset what I was going through at my desk. I loved reading, I loved learning, and many of the things that I was reading were driving me to ask different kinds of questions about my responsibility as a Black lawyer. I turned down the law firm when I was offered a position after graduation, and instead I enrolled in a Ph.D. program. I began to write about the civil rights struggles that I had heard about as a child and the issues I was experiencing as a Black law student and then lawyer. That has been the best professional decision I ever made. Today, there are sometimes late nights and early mornings I am working hard and attempting to be very productive, but the best part of it is that I am living my dreams every day. I am being the kind of person that I had hoped to be many years ago when I started law school – that I am doing social justice work.

H. Timothy Lovelace Jr., J.D., Ph.D

https://law.duke.edu/fac/lovelace/

Recent Courses at Duke

- 350: Advanced Constitutional Law: A Legal History of the Civil Rights Movement

- 587: Race and the Law

- 605: Race and the Law Speakers Series

Further Reading

“Making the World in Atlanta's Image: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Morris Abram, and the Legislative History of the United Nations Race Convention,” 32 Law & History Review 385 (2014)